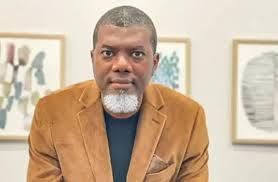

Philip Shaibu, the Edo state politician who was deputy governor in that state until yesterday afternoon, would seem to have failed woefully to learn certain basic lessons of power.

He has said that he is a victim of an act of injustice and that he would fight to the very end. He may have been led by his counsel to believe that he can fight this to the finish and get back his seat. He would be mistaken to be so misled. He had it coming. He has just been taught a few lessons in the dynamics of power play.

The 48 Laws of Power is the title of a book written by Robert Greene, an American author in 1998. It was a massive bestseller, selling over 1.2 million copies in the United States and even more worldwide, offering simple commonsensical advice, illustrated with narratives and historical examples to prove the point that power is a dangerous game, and only persons who understand its dynamics can survive in the palace. Greene recommends humility, obscurity and skilful navigation as the best skills for survival.

One of the reasons, Philip Shaibu, deputy governor of Edo state got impeached yesterday was due to hubris, defined in the literature as a flaw of character. And to worsen his agony, both the legislature and the executive further conspired to nominate, approve, and swear in a replacement, within hours after his impeachment, in the person of Omobayo Godwins from Ibilo, Akoko Edo, the oldest local government area in Nigeria, in specifically, Edo North where Philip Shaibu himself hails from.

In the power play that we have just witnessed in Edo state, it is clear that the intention of Governor Godwin Obaseki is to crush Philip Shaibu completely. He has publicly humiliated Shaibu and forced him to know who the master of the game is. Less than a week after Easter, days after the betrayal of our Lord Jesus Christ by Judas Iscariot, Shaibu, a Christian has just been made to remember, forcefully, Acts 1: 20 – “For it is written in the book of Psalms, let his habitation be desolate, and let no man dwell therein and his place let another take”. Yesterday, someone else took Philip Shaibu’s place in Edo state.

How did he get here? Philip Shaibu emerged in 2016 as the running mate to Godwin Obaseki in the gubernatorial election in that state that year. They both won on the platform of the All Progressives Congress (APC). Shaibu was the unanimous choice as Obaseki’s running mate. He had behind him, the support of Comrade Governor Adams Oshiomhole who was his political godfather and who left no one any choice in the matter. Shaibu and Oshiomhole are from the same homestead and senatorial district. The APC won the election and assumed office in November 2016. To be fair, Shaibu and Obaseki cut the perfect picture of a team. Many were surprised because it was unusual to have a governor and a deputy governor working together so peacefully like brothers. Shaibu was not just powerful, he was visible and influential. Whenever the governor went on vacation, he handed over the reins of power to his deputy.

In 2020, when ahead of the struggle for a second term, Obaseki fell out with his former mentor, Adams Oshiomhole and had to leave the APC to find a new political abode in the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), Shaibu stayed with his principal, the governor. The big men in the rival PDP did not want him as a running mate. They didn’t want him as part of the deal. But Obaseki and Shaibu were so much together that Obaseki insisted that Shaibu was part of the deal. He would not ditch him. He had his way. In 2020, Obaseki and Shaibu began a second term in office.

The deputy governor’s high moment came in 2021, when he led the National Sports Festival 2020, hosted by Edo state, as the chairman of the organising committee. Governor Obaseki was full of accolades for his deputy. The federal government did not provide the necessary funding, yet Edo state pulled it off, delivering one of the most memorable sports festivals many Nigerians had seen. Shaibu’s reputation as a go-to, can-do person soared. His political scorecard looked even brighter. At the University of Jos where he obtained a B. Sc degree in Accounting, he was president of the Students’ Union from 2000 -2001. In 2003, he was elected into the Edo State House of Assembly. He spent two terms representing Etsako West Constituency. In 2015, he won election into the Federal House of Representatives on the platform of the APC, representing Etsako federal constituency. Having served subsequently as deputy governor, and having been such a star in that position, Shaibu decided in 2023, that it was his turn to become governor and succeed his boss. The Edo governorship election is slated for September 21, 2024.

Shaibu defined his declaration and ambition as “a call to destiny”. This was the beginning of his problems. He did not have the support of his principal, Obaseki who thought, along with others that Edo North where Shaibu hails from, had had more than enough shot at the Government House position in Edo state. Oshiomhole, an Etsako man, was governor of the state for eight years. Shaibu, believed to be his relative even, was going to serve for eight years as deputy governor. A powerful lobby group in the state believes that the people of Edo Central should be given a chance. Since the return to democracy in 1999, only one person from Edo Central, Professor Oserheimen Osunbor had shown up as governor but even his tenure was truncated by the courts, paving the way for Adams Oshiomhole from Edo North. Whereas Governor Obaseki has insisted that he has no preferred candidate in the election, it was clear that he did not want his deputy to succeed him. Thus, the impression that Edo state had shown a better example in terms of the tumultuous relationship between governors and their deputies ended up as a mere illusion in the end. The fight between Shaibu and Obaseki turned messy and acrimonious, finally fitting into an established pattern with the impeachment of Philip Shaibu yesterday. It is unfortunate because it is so familiar.

The office of the deputy governor is a creation of the 1999 constitution to the extent that Section 187 (1) makes it clear that a candidate for the office of governor shall not be deemed to have been validly nominated unless he nominates another candidate as his associate for his running for the office, that is a deputy governor. The joint ticket nature of the gubernatorial process has been proved, beyond a scintilla of doubt in PDP and 2 ors v. Biobarakuma Degi-Eremienyo and 3 ors in the November 2019 Bayelsa governorship election. David Lyon could not become governor because of discrepancies in his running mate’s qualifications. Despite this twinning of the ticket, this Siamese-twins, umbilical cord connection between governors and their deputies, what has happened, since 1999, is that upon assumption of office, there has been no love lost between the duo. One reason is that the 1999 constitution does not expressly assign powers to the deputy governor. The governor, like the president at the federal level, is like a monarch. He controls everything. His word is law, and so everyone from traditional rulers to lawmakers in the State House of Assembly learns very quickly that the man to fear and worship is the governor, who claims that he is an “executive” or that he is a “constituted authority.

This “Kabiyesi” syndrome is the bane of Nigerian politics. The deputy governor gets a generous mention in Section 191 of the 1999 constitution which upholds the principle of jus accrescendi inherent in the joint ticket, to wit a deputy takes over in the event of death, resignation or incapacitation, but which is interpreted to mean that a deputy governor is a spare tyre waiting for the main tyre to develop a fault so it can be replaced and he, the deputy can become the main driver. In a superstitious country such as ours, a deputy governor is treated with suspicion. Any sign of self-expression or assertiveness on his or her part is seen as a sign of disloyalty. Political courters capitalise on this and have always tried to cause problems. When the deputy and the governor have different godfathers, the crisis is assured. It is rare to find any incumbent governor who openly encourages his deputy to succeed him. It happened in Zamfara once upon a time, but Alhaji Sani Yerima and his successor, Aliyu Shinkafi soon fell apart. Section 193 further reduces the role of a deputy governor to the discretion of the governor. What is the pattern is conflict in Government Houses in the states and even in the Presidential Villa to varying degrees.

For example, President Bola Tinubu as governor of Lagos state, from 1999 to 2007 had three deputy governors. Mrs. Kofo Bucknor-Akerele and Mr. Femi Pedro both have stories to tell. Dr Abdullahi Umar Ganduje served as deputy governor to Dr. Rabiu Kwankwaso (1999 – 2003, 2011-2015) but his former boss did not consider him good enough to succeed him. He got there by his means. They have remained tough adversaries since then in Kano politics. The late Christopher Alao-Akala, deputy to Governor Rashidi Ladoja became governor in 2006, only because his principal was impeached. Ladoja was reinstated by the Supreme Court in December 2006. Bala Ngilari became governor of Adamawa state in 2014 only because Governor Murtala Nyako was impeached.

In Ondo state, to cite a recent example, the late Governor Rotimi Akeredolu had issues with his deputies. In his first term, a certain Agboola Ajayi who was his deputy fell out of favour because he was eyeing the governor’s seat. His successor, Lucky Aiyedatiwa would also eventually run into trouble. He is the governor today because his principal died. At the state level, only 10 out of 149 deputy governors have taken over from their bosses since 1999, across the 36 states of the federation, and not necessarily because their bosses wanted them there. In Kebbi, Kano, Imo, Niger, Nasarawa, Plateau and Benue states, we have seen incumbent governors supporting candidates other than their deputies who stubbornly sought to succeed them.

Engr. David Umahi, now minister of works became governor of Ebonyi state in 2015 despite his former principal, Governor Martin Elechi, who insisted that Umahi was not his choice. At the federal level, the Obasanjo presidency became a “Bolekaja Presidency” because then Vice President Atiku Abubakar wanted to unseat his boss before the 2003 general election. Obasanjo’s second term was a divided presidency because the principal needed to teach his deputy a lesson. In 2010, it took the invocation of a doctrine of necessity to get then Vice President Goodluck Jonathan to succeed President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua first as acting president and later as president. Those who did not want Jonathan as president never gave up.

In sum, there is nothing unusual in the latest developments in Edo state. What must be noted is the sheer stubbornness with which Shaibu took on the war against his principal. In the process, he was banished from Government House and restricted to a corner of Benin City. His media crew was withdrawn. He was stripped of all responsibilities. He was told in no uncertain terms that he would not be governor. He went to court to defend his rights. He later withdrew the case. He apologised. But nothing changed. When the PDP held its party primaries, he organised his own event in his own house and declared himself as the chosen candidate. The next thing that came his way was the commencement of impeachment proceedings against him.

On the surface, the state house of assembly tried to follow the motions prescribed in Section 188 of the constitution on the removal of a governor or deputy governor from office. Shaibu and his lawyers claim that the House acted in violation of an ongoing process at a Federal High Court in Abuja. Without prejudice to Section 188 (10), the only remedy available to Shaibu is to prove in court that his removal was unconstitutional and seek to rely perhaps on Rashidi Ladoja’s case – see Muyiwa Inakoju and Ors. vs. Abraham Adeleke, Rashidi Ladoja and ors. (2007). But the times are different. The circumstances have changed. Shaibu’s political future hangs in the balance.

Whatever tricks his lawyers may still think they have in their bags, when Shaibu is alone let him reflect on how he ignored the laws of power. Law One says: “Never Outshine the Master”. Shaibu got so carried away that he began to sound as if he was the master of the governor. He openly boasted that without him Obaseki could never have been governor and that he funded his ambition and mobilised support for him. Obaseki has just shown him where power lies. He also violated the fourth law: “Always say less than necessary”. Shaibu believes that he can talk his way to the ticket for Osadebey House. Worse, he disobeyed Law 18: “Do not build fortresses to protect yourself. Isolation is dangerous”. Shaibu isolated himself. He parted ways with Senator Adams Oshiomhole who helped him to build his political career. He quarreled with party bigwigs like Dan Orbih. He abused elders and burnt bridges. He lacks the kind of support that propped up Dave Umahi in Ebonyi and Abdullahi Ganduje in Kano state. Isolation is indeed dangerous. Shaibu’s only saving grace would be how he stands in relation to Robert Greene’s Law 26: “Keep your hands clean”. Let us hope that his hands are clean.

Nonetheless, no man should be subjected to the kind of pain that he has had to endure simply because he wants to exercise his fundamental rights under the law. A system that turns governors into mini-gods who determine other people’s fate is deplorable. The sycophantic breed of commissioners, special advisers, lawmakers and courtiers who would do anything to please the governor of a state pose a serious threat to the democratic process. In the long run, Nigeria must make up its mind what it wants to do with the position of deputies: it is either we protect that office constitutionally by assigning specific powers, or we scrap it.